“Fardad is dead,” she said. My mother broke the news to me that my cousin Fardad, along with 18 other Iranian youth, were indiscriminately targeted by a missile attack, and consequently, they all tragically perished. Apparently, they were riding in a truck at the time, approaching the Turkish border. To this day, nobody knows why the missiles were even fired in the first place. In the midst of a climate of ethnic conflict between the Kurds and the Turks in the eastern part of Turkey—a region far too familiar with violence and conflict as memories of the Armenian genocide of the Ottoman empire still mark the site, however, any root cause could have been "plausible" (yet unjustified). The truck was just a few kilometers away from the UN refugee camp, where the youth would have temporarily settled in the hopes of eventually finding a university that would admit them for study. I was 17 years old when this was all recalled to me, and Fardad was 19 on the day of his untimely death.

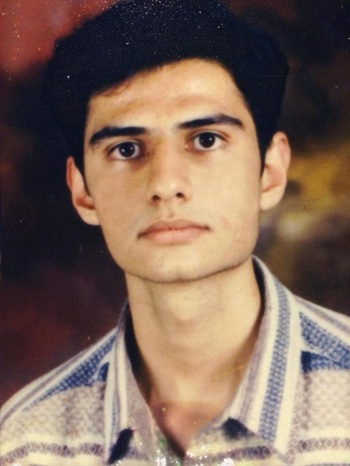

I never had the pleasure of meeting Fardad, but from what I learned of him from my mother and father and his mother and father, he had an amazing, selfless spirit. I learned he never smiled in photographs, even as a child, which explains the solemn expression on his face in the photo above. I only “knew” him through photographs that were sent to us in Long Beach, California from Tehran. I can't even recall if we had ever spoken to each other by telephone (in spite of my self-conscious “American accent” that surfaced whenever I spoke Persian to family members living in Iran, whom I had never met except through the exchange of decorated Persian colloquialisms and phrases). Whether or not I ever spoke to Fardad, however, didn't really matter. It wasn't relevant, because I “heard” him through his actions. Years later, I learned from his mother that Fardad was actually admitted to university after successfully passing the national entrance exam, the concours, required of all students in Iran who wanted to attend university. However, since most of his Bahá’í friends were denied admission or being expelled in the midst of their university studies, he refused to pursue higher education that denied him and his peers access solely on the unfounded basis of religious identity. Fardad’s actions and consequent death transformed my perceptions of the meaning and implications of education, particularly by questioning my own motives for pursuing any level of formal education.

Just as I had noticed in Fardad, faith is one of the most vital qualities that has deeply rooted and strengthened the Iranian Bahá’í community, which comprises the largest religious minority in the country with approximately 300,000 adherents. For over 30 years, members of the Bahá’í community in Iran have experienced inexplicable persecution by the government. One of the state’s most ongoing attempts in thwarting the progress and stifling the development of the Bahá’í community, has been through the methodical barring of higher education to Bahá’í students and faculty throughout the country.

Although Bahá’í students and faculty were expelled from universities as early as the mid-1980s, the systematic exclusion of Iranian Bahá’ís from accessing higher education was actually revealed in a confidential memorandum drafted by the Iranian Supreme Revolutionary Cultural Council (ISRCC) in 1991. The primary purpose of the memorandum was to emphasize an intentional treatment of Bahá’ís so that “their progress and development are blocked.” The memorandum also states that “[t]hey must be expelled from universities, either in the admission process or during the course of their studies, once it becomes known that they are Bahá’ís.”

Rather than arise in disobedience or protest against the government, the Iranian Bahá’í community responded with what a New York Times article described as “an elaborate act of communal preservation” and what the Bahá’í International Community (BIC) referred to as “remarkably creative—and entirely non-violent”—the establishment of its own higher education institution to serve the needs of Bahá’í students who aspired to pursue a university education. This institution—currently identified as the Bahá’í Institute for Higher Education (BIHE)—was created in 1987, and since 1996, its supporters have endured occasional government raids, arrests, incarceration, torture, destruction of equipment, and the vandalism of offices and homes, where BIHE courses are often held. I think Michael Karlberg said it best when he referred to the BIHE as a “non-adversarial model” that wholeheartedly characterizes “constructive resilience.”

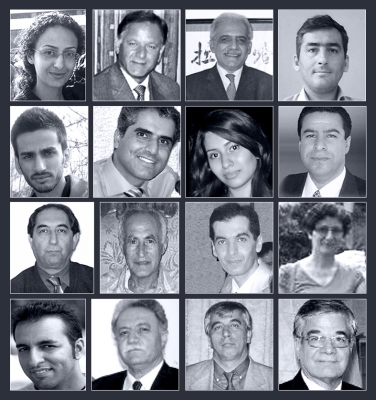

May 21, 2011 marked the most recent in a series of (discovered) events in which the government again interfered with BIHE activities, raiding 33 homes and arresting 16 individuals and interrogating eight others—all due to their involvement with the BIHE. The goal of the government, in making these arrests, was to shut down the functioning of the BIHE and to prevent the development and progress of the Iranian Bahá’í community, as indicated in this news story. Administrators at the BIHE were accused of using the BIHE as a front for spreading Bahá’í teachings or “false propaganda.”

Despite what some might assume or understand regarding the motives behind the BIHE, the purpose of the institution is solely to provide an education equivalent to the national standards of the country. The only difference is that it is not accredited, because it is not recognized by the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology (MSRT), the ministry that oversees most of higher education throughout the country. Over 1,000 students have already “graduated” from the BIHE (as no formal degrees are conferred), where 18 programs in various disciplines—at the undergraduate and graduate levels—are offered, and all courses are taught by faculty members on a completely voluntary basis.

Are doctorate degrees untouchable, unfathomable, unreachable, unpredictable . . . or are they just plain unappealing? I think Ph.D. degrees can easily be all of these things, depending on who you “are” and where you “come from” in spite of who and where you aspire to be. Fardad, for example, had a ZERO percent chance of receiving a Ph.D. in Iran, let alone a bachelor’s degree. The fate of Fardad and his companions' wasn't an isolated incident, however. There are countless cases in which systematic and unmethodical barriers prevent peoples and groups all over the world from equally and equitably accessing higher education (and the U.S. is definitely not an exception). Meanwhile, here I am, contemplating the trivial matters that accompany the doctoral degree at a "flagship" research institution based in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States: Why does it cost $220.98 to rent doctoral regalia and $964.98 to buy it? . . . Even in preparation for my upcoming dissertation defense, I am entranced by the subtle yet smack-you-in-the-face irony of my research topic. Its visual implications are reflected on the title page I chose for my PowerPoint presentation, and for the first time, I "see" myself in relation to those arms that are reaching, extending, aspiring.

More information about the BIHE and the systematic exclusion of Bahá’í s from accessing higher education in Iran is available in a special report published by the BIC entitled Closed Doors: Iran’s Campaign to Deny Higher Education to Bahá’ís.